Under the leadership of Anna Szécsényi-Nagy (HUN-REN Institute of Archaeogenomics) and Zsuzsanna Siklósi (MTA-ELTE “Lendület” Innovation Research Group), we have published a new archaeogenetic study on the populations of the Great Hungarian Plain in the Neolithic and Copper Age.

Working in an international team, we carried out comprehensive analyses on 125 prehistoric human genomes extracted at the University of Vienna and Harvard Medical School. The genomes come from Carpathian Basin populations that lived on the Great Plain during the Late Neolithic and Early Copper Age. Archaeologists from ELTE’s Institute of Archaeological Sciences, the Satu Mare County Museum (Romania) and the Budapest History Museum, as well as anthropologists from the Hungarian Natural History Museum and ELTE’s Faculty of Science, took part in the research.

The study focused on the Polgár region along the River Tisza, where well-documented excavations have made it possible to examine Neolithic and Copper-Age communities. We combined population genetics, kinship analyses and networks built from shared IBD (identity-by-descent) autosomal haplotype segments with archaeological and anthropological observations. These tools gave us a clearer picture of social and biological organisation and dynamics between 4800 and 3900 BC.

Despite drastic social change indicated by archaeological data in the transitional period 4500–4350 BC—and a 300-year gap between the two key sites Polgár-Csőszhalom and Tiszapolgár-Basatanya—we detected fundamental biological continuity among people around Polgár. At the end of the Neolithic long-lived tell settlements were abandoned in favour of small farm-like hamlets, burials moved from beside houses into new cemeteries, and everyday artefacts changed markedly.

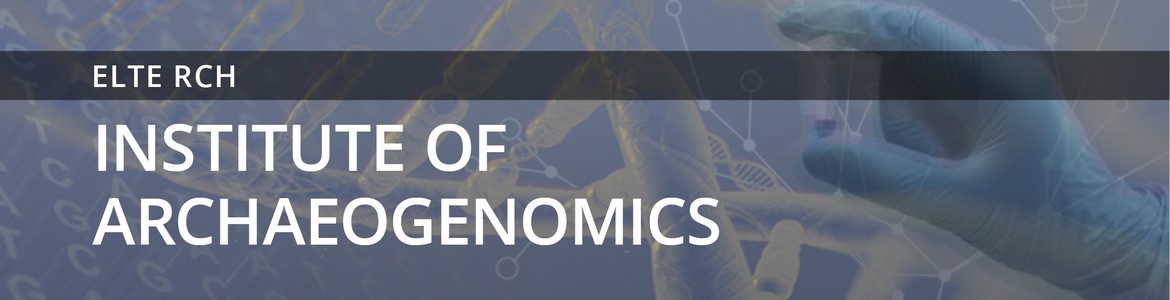

Late Neolithic burials from Polgár-Csőszhalom (1-2) and Early Copper-Age burials from Tiszapolgár-Basatanya (3-6) (after Raczky et al. 2014, fig. 5.)

Late Neolithic burials from Polgár-Csőszhalom (1-2) and Early Copper-Age burials from Tiszapolgár-Basatanya (3-6) (after Raczky et al. 2014, fig. 5.)

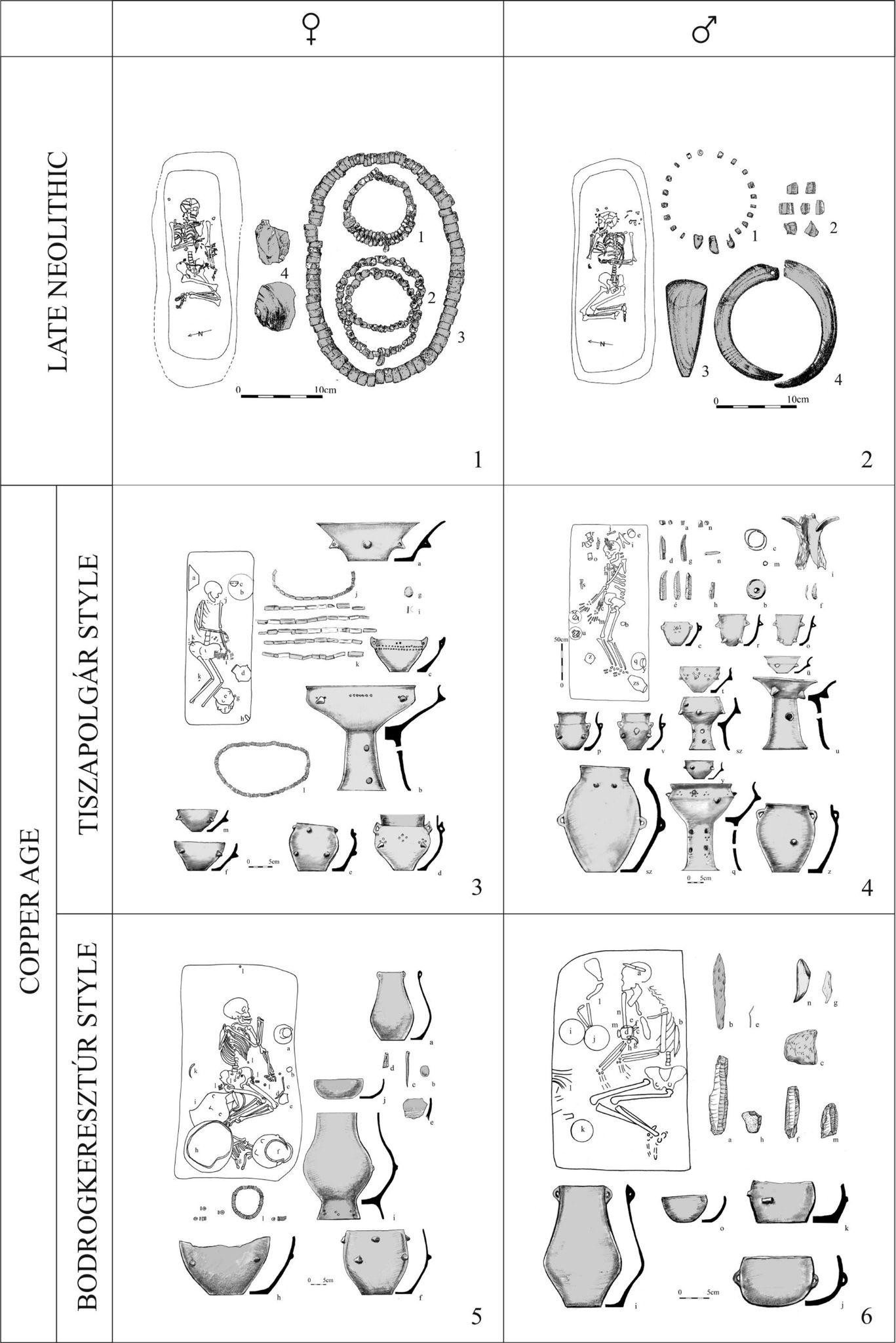

Whole-genome data let us now build networks from distant biological links, revealing spatial and temporal dynamics of personal connections. The Early Copper-Age cemetery of Tiszapolgár-Basatanya (4350–4000 BC) proved particularly intriguing. Until now we have not known how individuals using different pottery styles were biologically related, or their mate-choice and burial preferences. The new study shows that people employing partly overlapping but sequential ceramic styles were kin. The cemetery formed a biologically closed community probably isolated in cultural terms, evidenced by frequent cousin marriages and dense internal genetic ties.

Biological kinship network and reconstructed family trees, Tiszapolgár-Basatanya

Biological kinship network and reconstructed family trees, Tiszapolgár-Basatanya

Families at Basatanya followed paternal descent: men founded new households where they had grown up, maintaining their ancestral burial grounds. Women formed most external links, though systematic female exogamy is not evident.

Copper-Age burials from Urziceni-Vamă

Copper-Age burials from Urziceni-Vamă

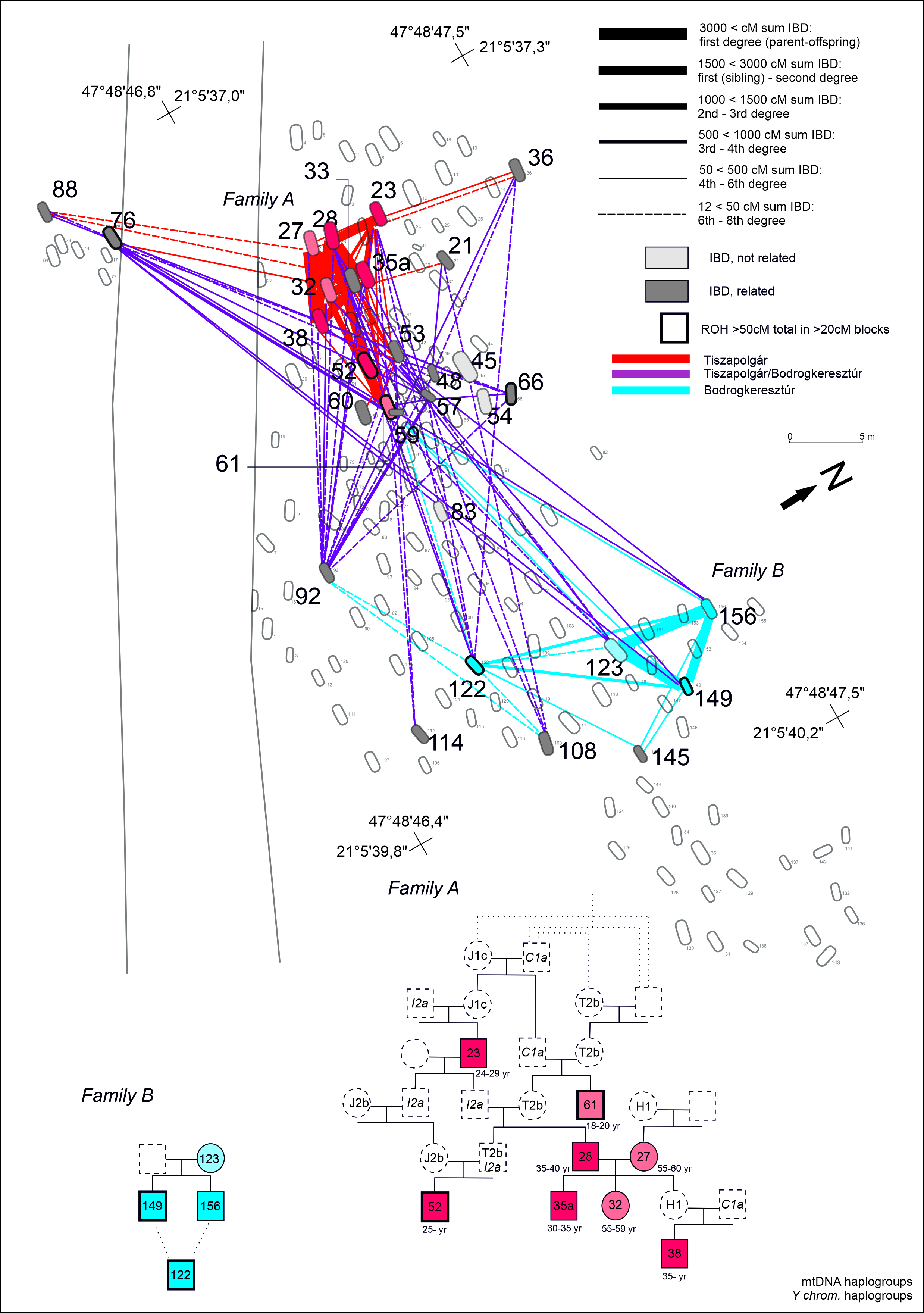

Regional comparison already shows contrasting patterns. Genetic relationship networks have revealed that Early Copper-Age communities on the Great Plain were organised according to markedly different systems. At contemporary Urziceni-Vamă, only ~100 km away, the structure was different: fathers are largely absent from small family units, close relatives were often buried apart, cousin marriages are lacking and genetic links are wider—suggesting a community estimated six times larger than that at Tiszapolgár-Basatanya.

Biological kinship network and reconstructed family trees, Urziceni-Vamă

Biological kinship network and reconstructed family trees, Urziceni-Vamă

The MTA-ELTE “Lendület” group and HUN-REN Institute of Archaeogenomics are continuing bioarchaeological work on Tiszapolgár-Basatanya to refine our understanding of cemetery layout, family structure and the biological processes behind Early Copper-Age social change.

Press publications:

Der Standard: Was Skelette über geschlossene Gemeinschaften vor 7000 Jahren verraten

ORF.at: Gesellschaftsentwürfe vor 7.000 Jahren

Salzburger Nachrichten: Forscher zeigen verschiedene Gesellschaftsentwürfe vor 7.000 Jahren