A new study from our institute provides a significant step towards elucidating the genetic narrative of the Persian Plateau during the prehistoric and historic periods.

The Persian Plateau has been an important region for humankind since the ancestors of the non-African peoples left their African homelands, which led to the colonisation of the rest of the Earth by the Homo sapiens (aka modern humans). Since then, modern humans have continuously inhabited the Persian Plateau, benefiting from its resourceful conditions and making the Plateau one of the areas where farming practices were first developed. These suitable circumstances then helped several ancient civilisations to rise and expand. For thousands of years the human groups within the Plateau engaged in internal and external contacts such as trade and cultural exchange, culminating in the formation of the Silk Road by the 1st century BCE, when the Persian Plateau became a crucial bridge between the East and the West. By this date, the region had already seen the formation of the Achaemenid Empire as the largest empire ever formed at the era of its existence, the conquests of its territories by the Macedonian Empire and the emergence of the Hellenistic world, and then the Parthian Empire’s dominance, which carried the region towards and through the early stages of the Common Era. Finally, the Sassanids rose with the aim of reinstating the glory of the Achaemenid times and ruled the Plateau until the 7th century CE. While ancient historical records show these clear political changes in the Persian Plateau, the fates of the common people are often overlooked by those sources.

Our new study published in Nature Scientific Reports on 13th May 2025 provides new insights into the genetic histories of the Plateau’s populations. We presented the 13 newly-analysed genomes and 23 mitochondrial genomes from samples with sufficient DNA sequence coverage taken from a total of 50 ancient individuals, whose remains were excavated from nine sites located in the territory of modern Iran. Among the individuals with newly-produced genomes, one crucial Early Chalcolithic period male and a Medieval female were excavated from around the Zagros Mountains, while the other eleven individuals were from the historical period in the northern Iranian region, inhabiting the area during the Achaemenid-to-Sassanid epoch. The research was conducted through a collaboration between the HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities (RCH) Institute of Archaeogenomics, Kawsar Human Genetic Research Centre, The Research Institute of Cultural Heritage and Tourism of Iran (RICHT), The National Museum of Iran, and the Falak-ol-Aflak Museum, University of Tehran.

Our findings indicate substantial genetic continuity in the Persian Plateau (albeit with relatively minor changes and regional differences) in an atmosphere of constant cultural and political change. Many Y-chromosomal and mitochondrial DNA lineages (called uniparental lineages due to the respective patrilineal and matrilineal descent patterns) were discovered to be continuous over centuries and are now present in the modern groups of the region as well.

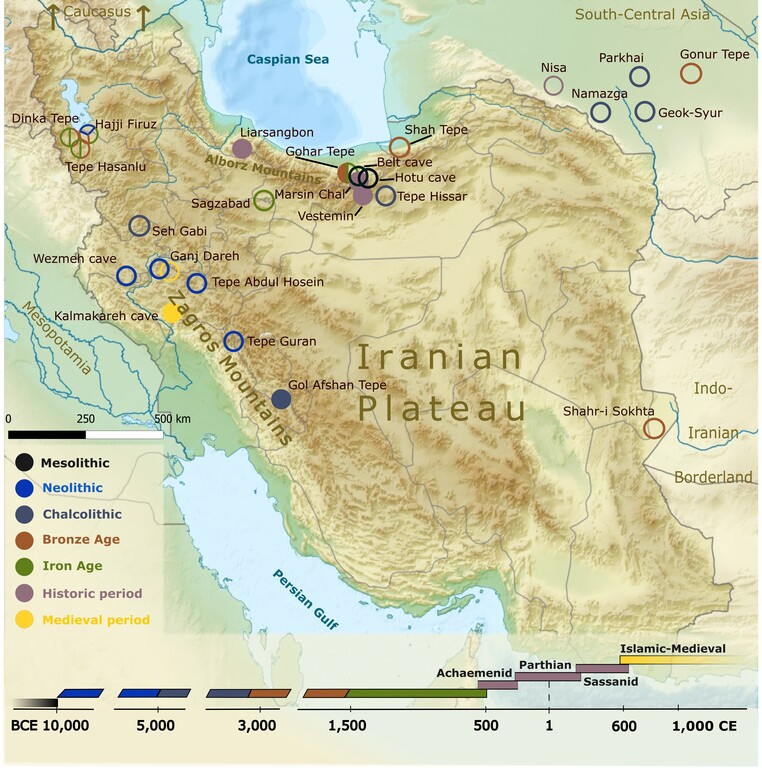

Fig. 1: Map of the Iranian Plateau and its surroundings. Present-day Iran is highlighted, with the archaeological sites mentioned in the text. Filled circles represent new samples, empty circles mark sites from which ancient DNA data has been published in previous studies. Created by Anna Szécsényi-Nagy.

Fig. 1: Map of the Iranian Plateau and its surroundings. Present-day Iran is highlighted, with the archaeological sites mentioned in the text. Filled circles represent new samples, empty circles mark sites from which ancient DNA data has been published in previous studies. Created by Anna Szécsényi-Nagy.

It has been known since 2019 (Narasimhan et al. Science) that the genetic composition of the prehistoric groups in the Persian Plateau was part of a genetic cline that spanned the whole region in an east-west direction, and this cline persisted into the historical era as found in the new dataset. The Mesolithic Caucasus hunter-gatherers and Iranian Neolithic farmers contributed to the succeeding groups in the region, and our new findings together with a comprehensive review of previous data now increase the resolution of our understanding regarding the contribution of these peoples to their genetic “descendants”. The newly-published Early Chalcolithic individual from Gol Afshan Tepe predates all previously published Chalcolithic Iranian genomes, and it is evident that the Neolithic-Chalcolithic transition came with a major contribution from the local farmers, while there was also an input from more westerly populations. In other parts of the Plateau, however, we describe varying degrees of genetic traces left by Caucasus hunter-gatherers and the Iranian farmers, referred to as “dual ancestries” originating from both ancestral populations. We also report the possible presence of a previously undescribed genetic component in the Neolithic-Chalcolithic Iranian farmers, which is genetically distinct but whose source is not yet characterized.

Fig. 2: Gohar Tepe site, Behshahr, Mazandaran province, Iran. Inhumation burial from the Late Chalcolithic to Middle Bronze Age period (3100-2300 BCE). Photographed by Dr. Ali Mahfroozi.

The historical period peoples of the northern Iranian region had most of their ancestries from the Neolithic-Bronze Age groups of the Persian Plateau. Most importantly, the historical period northern Iranian individuals did not exhibit detectable admixture from the Bronze Age steppe pastoralists. Instead, we discovered long term genetic connectedness between the Iranian region and South-Central Asian regions (Turkmenistan and its surroundings) as most of the ancestries of the northern Iranian groups could be represented with the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex’s peoples and their descendants. This culture (often called the BMAC or Oxus Civilization) was one of Central Asia’s major urbanized Bronze Age societies, flourishing between 2400 and 1700 BCE in what is now Turkmenistan, northern Afghanistan, and southern Uzbekistan. However it should not be forgotten that this sample set represents only a limited portion of the Plateau and future studies from other areas may provide more insights into the genetic role of the steppe pastoralists. Notably, a recently published article (Ghalichi et al. Nature, 2024) had two Bronze Age individuals from the same region where we sampled the historical period northern Iranian individuals from. Those samples were also modelled without any steppe ancestry in the study, and seem genetically similar to the historical period individuals, however we could not incorporate them to our study since they were published at a late stage of our project.

Fig. 3: Liār-Sang-Bon site, Amlash, Gilan province, Iran. Inhumation burial from the Parthian period (burial no. 96304). Findings include materials of daily life and war armaments. Photographed by Dr. Vali Jahani.

The Kalmakareh Cave stands as a remarkable archaeological site, yielding a trove of ancient gold treasures originally deposited in the 7th century BCE—a period associated with the influence of civilizations like the Elamites. The discovery of human remains alongside these valuable artefacts initially fueled speculation, with theories suggesting they might have been ancient guardians or even distinguished owners from the Late Elamite period. However, the new radiocarbon (14C) dating has unveiled a far more unexpected and intriguing scenario. Rather than being contemporaries of the treasure's origin, the human remains date to the 12th century CE. This striking Medieval finding recasts these individuals as concealers of the ancient hoard, interacting with it nearly 1900 years after the treasures' original date in the Neo-Elamite period. Currently, the Medieval period in the Iranian region is represented in the ancient genome databases by only two available individuals, one of whom is published in our new study from the Kalmakareh cave. On the other hand, these Medieval people and the modern Iranian peoples such as the Persian (Farsi) and Mazandarani-speaking groups demonstrate the variety within the Persian Plateau. It is therefore currently plausible to suggest that these groups also genetically descend from the more-ancient peoples in the region; however, further research is required to draw definite conclusions.

Fig. 4: Hidden Elamite treasure of the Kalmakareh Cave: a silver rhyton. Kalmakareh in Persian means the dwelling or resting place of the male mountain goat and fig tree. The cave’s name reflects its location in the mountains of Lorestan Province in Iran. Photographed by Dr. Leila Khosravi.

The research was supervised by Anna Szécsényi-Nagy (HUN-REN RCH Institute of Archaeogenomics) and Mahmood Tavallaie (Kawsar Human Genetic Research Centre), with contributions from 16 co-authors. It was led by Motahareh Ala Amjadi Ph.D. student of the Eötvös Loránd University and was carried out at the HUN-REN RCH Institute of Archaeogenomics.

Fig. 5: Sampling of the human remains by Motahareh Amjadi. Vestemin archaeological site, Kiasar, Mazandaran Province. Samples, taken directly during the excavation campaign, are from the Parthian to Sassanid Periods.

📌 Link to the study in Nature Scientific Reports

New genotypes (Chr. 1-22 of the 1240k SNP panel) of this study are available here.

The DNS sequences are available in BAM format on the ENA website.

📩 Further information: