Recovering population events of the Migration Period in the Carpathian Basin to the finest details has been obstructed by earlier archaeogenomic methodologies due to its enormous complexity.

By the mid-2020s, advances in modern technology and expanding genetic databases have enabled researchers to trace back connections between groups in “real time”, identify distant relatives, and detect sources from a biological perspective.

Our research, initiated in 2018 under the Árpád Dynasty program supported by the Ministry of Human Resources, aimed to provide a genetic description of 8th–11th century populations from Transdanubia (western Hungary) and to contribute both international and Hungarian genetic databases. Additionally, we sought to gain insights into population genetic events in the Carpathian Basin by co-analysing the new dataset with previously studied individuals and groups from Hungary belonging to the same period.

In total, we analysed 296 human remains from 7th–11th century cemeteries in Transdanubia, along with a sample from Uyelgi (east of the Ural mountains) linked to early Hungarians (Csáky et al., 2020b). In our study, we generated 103 complete autosomal genomes, which, combined with previously published datasets (Amorim et al., 2018; Gnecchi-Ruscone et al., 2022; Maróti et al., 2022; Vyas et al., 2023), formed a database of more than 400 high quality samples from the second half of the 1st millennium CE Carpathian Basin.

During data analysis, we were among the first to apply the IBD (identity-by-descent) method (Ringbauer et al. 2024), and used to reveal DNA segments (chromosome blocks) that trace back to a common ancestor shared by two or more individuals. This method allows the exploration of complex biological networks by bridging the gap between the levels of direct kinship and broader population genetics connections. The former could only detect close kin relations (e.g., up to third-degree relationships, such as cousins), while the latter addresses broader population genomic questions, such as estimating the source region of groups like the eastern origin Avar period elite. The IBD approach, however, reveals more distant, yet socially significant relationships (e.g., second cousins) and also helps disentangle ancestry components or identify a common ancestor within a timeframe of a few hundred years. For example, it can determine whether eastern origin Avar period elite and the early Hungarians were directly related or merely shared deeper common ancestry.

Our sampling focused primarily on the transitional period between the Avar Khaganate (568–811 CE) and the foundation of the Hungarian Kingdom, aiming to shed light on this less understood but historically rich era.

Key findings and their implications:

- Genetic characterisation of the European origin Migration Period population in the Carpathian Basin:

While European groups underwent significant cultural and genetic changes from the Palaeolithic to the present, the genetic structure established after the introduction of steppe ancestry during the Indo-European migrations, and its subsequent admixture with local Copper Age populations about 5,000 years ago has remained largely stable. The populations of the Carpathian Basin, despite the continuous immigration since the Prehistoric Period, also fit into this overarching pattern.

This research represents a critical step forward in understanding the genetic history of the Carpathian Basin and its place within European population dynamics. More detailed insights and interpretations are provided in the paper itself.

|

|

While Europe maintained a relatively stable genetic composition over the centuries, regional-level internal reorganisations can be observed. One of the most striking examples is the temporal shift in the proportions of groups displaying southern and northern genetic characteristics during the second half of the 1st millennium CE. Generally, a homogenisation process can be observed from the 5th to the 11th century CE, peaking in the time of the Hungarian conquest. The composition of the 11th century CE population already largely resembles (but not equals to) those of the modern-day Hungarians.

The IBD (identity-by-descent) method revealed a further internal shift and discontinuity within the northern-characteristic European individuals. Members of this genetic group in the 5th–6th centuries CE, who were primarily recovered from Lombard archaeological contexts, show limited continuity with seemingly highly similar individuals from the 7th century from various archaeological contexts, suggesting a population turnover in this period.

|

|

Future research on population reorganisation

Understanding the details of this reorganisation will be the subject of future research. However, based on previous publications (Amorim et al., 2018; Olalde et al., 2023; Vyas et al., 2023), it can be hypothesised that the observed phenomenon is linked to the distinctions of Germanic and Slavic populations.

- Revisited Relationships Between Huns, Avars, and Early Hungarians, and Their Connections to the local population of the Carpathian Basin

Using the new IBD method, we have confirmed that the genetically East-Eurasian-characteristic individuals of the Hun period in the Carpathian Basin (commonly referred to as "Huns," although the association of ethnicity and biological ancestry remains controversial) show no biological succession or connection into the 10th conquering Hungarian population.

Our findings, consistent with previous studies (Csáky et al., 2020a; Gnecchi-Ruscone et al., 2022, 2024; Maróti et al., 2022), suggest that the East-Eurasian origin Avar period elite who appeared in the Carpathian Basin after 568, exhibit widespread endogamy (lacking inbreeding) in both genetic and likely social terms. Their intermixture (marriage and reproduction) with local populations was minimal, and showed virtually no succession in the conquering Hungarians, apart from a few exceptions.

Similarly, our results do not support a shared genetic origin of the eastern-origin Avars and conquering Hungarians. The lack of genetic continuity and the significant differences in their social organisations further weaken theories on their direct connection and continuity.

|

|

- The local population of the Carpathian Basin and its connections with the Avars and conquering Hungarians

Genetic data reveal that the Avars, who arrived from the Eurasian steppe, included populations of Eastern-Eurasian origin. They constituted roughly one-fifth of the gene-transmitting population of the Carpathian Basin in the 7th–8th centuries. An intriguing finding is that the archaeological disappearance of the Avars in the 9th century is mirrored in the genetic data, suggesting that the conquering Hungarians entered a Carpathian Basin with a predominantly European-like local population and a negligible presence of Eastern Avar genetic components.

Our genetic calculations estimate that the arriving eastern Hungarians to be about 10% of the Carpathian Basin's contemporaneous population. Assuming a local population of approximately one million (based on limited available data), the number of incoming Hungarians likely ranged between 100,000 and 150,000 individuals, in line with previous estimates based on historical sources (Juhász, 2015).

In contrast to the Avars, the Hungarians actively intermingled with the locals upon their arrival. This highlights differences in the societal structures of the two groups and raises a potential explanation for the succession of Hungarians, rather than the Avars both genetically and culturally in the following centuries.

- Individuals associated with early Hungarians (Magyars) were present in Transdanubia before their conquest

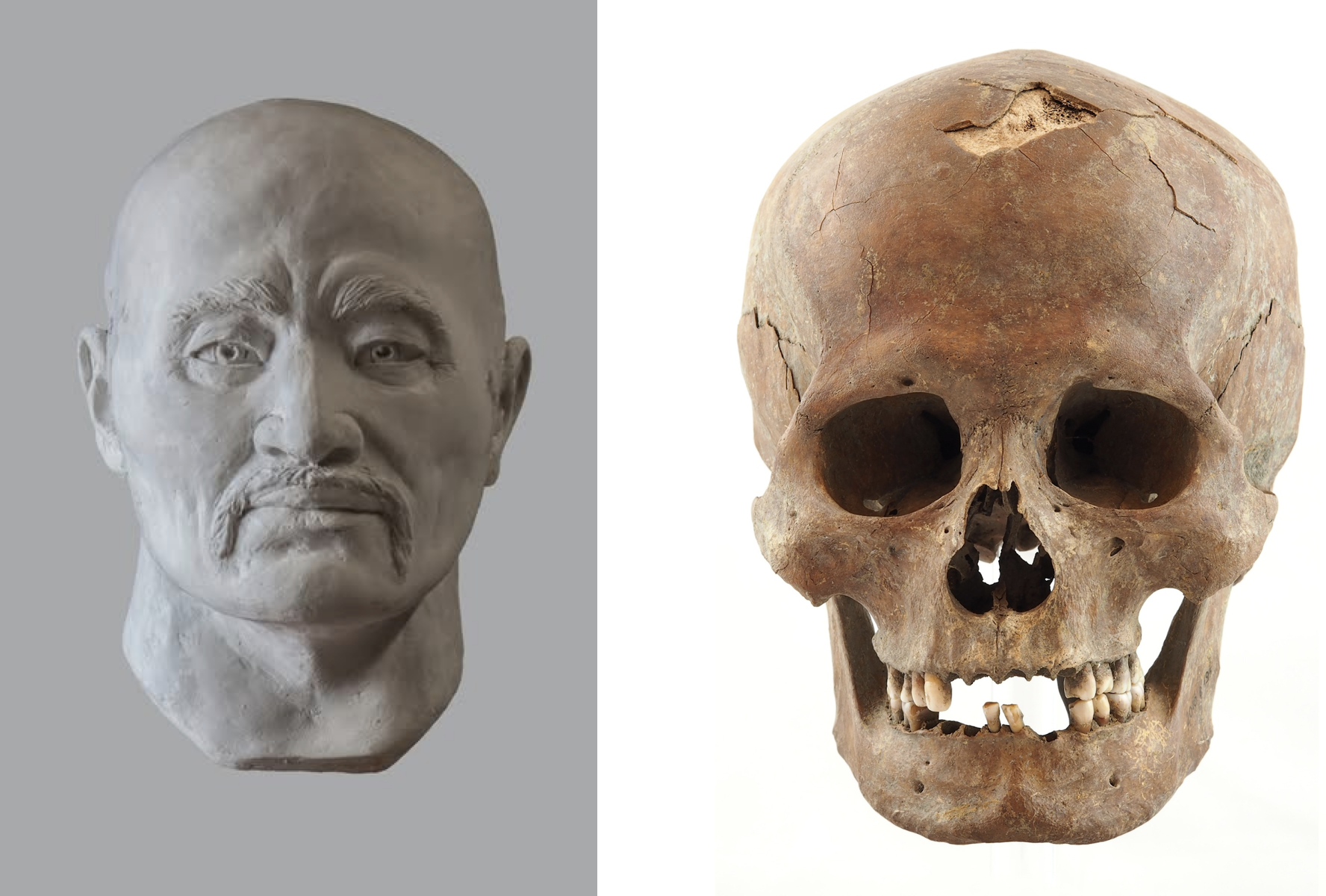

At the Zalavár-Vársziget site, in the multi-layered cemetery near the pilgrimage church of St. Hadrian, built in the late 850s CE, a male individual was buried during the 870–890 period and was classified as belonging to the genetic group of the Hungarian conquerors (grave 8/00, genetic code AHP21).

Moreover, AHP21 was found to have a fifth-degree genetic relationship with a male individual from Kenézlő-Fazekaszug (KeF-10936), a Hungarian conqueror burial site dated to the early 10th century. This level of relationship typically corresponds to a second-cousin relationship within the same generation, though temporal offsets may indicate an alternative type of kinship.

This finding supports the theory that Hungarians could have appeared in various western territories even before their large-scale conquest, possibly as members of armed contingents in the Carolingian period.

Facial reconstruction of the individual buried in grave 8/00 (AHP21)

Facial reconstruction of the individual buried in grave 8/00 (AHP21)

Created by Emese Gábor.

Source: Official Facebook page of the Hungarian Natural History Museum.

- Transformations of the populations of the Carpathian Basin between the 6th and 11th centuries CE

Based on the results of IBD analysis, several significant population events were revealed in the Carpathian Basin:

- The altered marital and relational patterns of the Avars in the 7th century (consistent with the findings by Gnecchi et al., 2024).

- The isolation between the populations of Transdanubia and the Great Hungarian Plain prior to the Hungarian conquest.

- The mass arrival of the Hungarians at the beginning of the 10th century, followed by population movements that reorganised the demographics of the entire Carpathian Basin.

Our results indicate that the presence of the Hungarians at the end of the 9th and the beginning of the 10th century was concentrated in the Great Hungarian Plain. By the latter half of the 10th century, not only the conquering Hungarians but also part of the local population of the region migrated to Transdanubia. During this second phase, previously isolated small local groups—some of which had persisted biologically since Roman times—began to disappear.

Our findings uncover complex population events at both macro- and micro-regional levels in the Carpathian Basin. While the primary goal of our study was to explore local population genetic events in the studied period, the co-analysis of external groups to reveal the origins of the Hungarians or some other local populations, was not in the focus of this research. Instead, these aspects form the basis of future studies.

This publication, which is the culmination of six years of research, was lead by Dániel Gerber, Veronika Csáky, and Bea Szeifert, and supervised by Anna Szécsényi-Nagy and Béla Miklós Szőke. We would like to express our gratitude to all researchers and co-authors (archaeologists, biologists, and historians) who contributed to this study. Special thanks go to our partners at the HUN-REN Institute of Archaeology, HUN-REN Institute for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, HUN-REN Wigner Data Center, Hungarian Natural History Museum, Hungarian National Museum, Rómer Flóris Art and History Museum, Szent István Museum, and Mátyás Király Museum in Visegrád.

Research support:

- Anthropological and Genetic Study of the Árpád-Era Hungarians. Árpád-Ház Program (2018–2023), Fundamental Scientific Program V.1. Project ID: 39509/2018/KFSZ.

- HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities.

- ELKH/HUN-REN Priority Research Topics: Archaeogenomic Research of the Etelköz Settlement Area.

- Szilágyi Family Foundation.

- HUN-REN Cloud System.

The full study on which this summary is based can be read here:

Gerber D., Csáky V., Szeifert B., et al. (2024). Science Advances.